TEV-Protease

| TEV-Protease | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

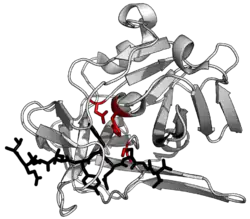

| TEV-Protease (weiß) komplexiert mit einem Peptidsubstrat (schwarz), katalytische Triade (rot) (PDB 1lvb) | ||

| Bezeichner | ||

| Externe IDs |

| |

| Enzymklassifikation | ||

| EC, Kategorie | 3.4.22.44 | |

Die TEV-Protease (EC 3.4.22.44, nuclear-inclusion-a Endopeptidase des Tobacco Etch Virus) ist eine Cysteinprotease aus dem Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV).[1] Sie gehört zur PA-Klasse der Chymotrypsin-artigen Proteasen. Aufgrund ihrer hohen Sequenzspezifität wird sie häufig zur kontrollierten Spaltung von Fusionsproteinen sowohl in vitro als auch in vivo eingesetzt.[2] Die erkannte Konsensussequenz ist Glu-Asn-Leu-Tyr-Phe-Gln-|-Ser, wobei "|" die Spaltstelle bezeichnet.[3]

Herkunft

Das Tobacco Etch Virus kodiert in seinem Genom ein einziges großes Polyprotein (350 kDa), das durch drei virale Proteasen (P1, HC, TEV) an spezifischen Stellen gespalten wird. Die TEV-Protease ist für sieben dieser Spaltstellen im Polyprotein zuständig.[1] Die TEV-Protease besitzt auch eine interne Selbstspaltstelle, deren physiologische Funktion unklar ist.

Struktur und Funktion

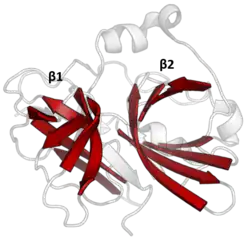

Die Struktur der TEV-Protease wurde mittels Röntgenkristallographie aufgeklärt.[4] Sie besteht aus zwei β-Fässern und einem flexiblen C-terminalen Schwanz. Die Protease gehört zur Chymotrypsin-Superfamilie (PA-Klasse, C4-Familie nach MEROPS).[5] Trotz Homologie zu Serinproteasen verwendet sie eine katalytische Triade bestehend aus Asp-His-Cys, wobei Cystein das nukleophile Zentrum bildet.[6] Das Substrat bindet als antiparallele β-Strang-Struktur in einer Tunnel-Region zwischen den Fässern.[7]

Spezifität

Die native Spaltsequenz ist ENLYFQ\S.[3] Die Aminosäuren vor der Spaltstelle werden als P6 bis P1, die danach als P1' usw. bezeichnet. Strukturstudien zeigen eine umfangreiche Interaktion zwischen Substrat und Enzym, wodurch eine hohe Spezifität erreicht wird. Die Bindetasche erkennt insbesondere P6-Glu, P4-Leu, P3-Tyr, P2-Phe, P1-Gln und P1'-Ser.[4]

Anwendung

Die TEV-Protease wird zur Entfernung von Protein-Tags bei rekombinanten Proteinen verwendet. Aufgrund der hohen Spezifität ist sie auch in vivo relativ ungiftig.[8] Rationales Design war bislang wenig erfolgreich, jedoch konnte durch gerichtete Evolution die Substrattoleranz erweitert werden.[9][10][11][12]

Einschränkungen

Die Wildtyp-TEV-Protease zeigt:[13]

- Autoproteolyse (durch Mutation S219V vermeidbar)

- Geringe Löslichkeit (verbessert durch MBP-Fusion oder Mutationen)[2]

- Temperaturinstabilität unter 4 °C oder über 34 °C[14]

- Reduktionsbedürftigkeit für hohe Aktivität (moderne Varianten sind auch ohne Reduktionsmittel aktiv)[15][16][17]

Weblinks

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ a b UniProt: TEV polyprotein: UniProt Tobacco etch virus (TEV)

- ↑ a b Kapust RB, Waugh DS: Controlled intracellular processing of fusion proteins by TEV protease. In: Protein Expr. Purif. 19. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, Juli 2000, S. 312–8, doi:10.1006/prep.2000.1251, PMID 10873547 (englisch).

- ↑ a b Carrington JC, Dougherty WG: A viral cleavage site cassette: identification of amino acid sequences required for tobacco etch virus polyprotein processing. In: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85. Jahrgang, Nr. 10, Mai 1988, S. 3391–5, doi:10.1073/pnas.85.10.3391, PMID 3285343, PMC 280215 (freier Volltext), bibcode:1988PNAS...85.3391C (englisch).

- ↑ a b Phan J, Zdanov A, Evdokimov AG, Tropea JE, Peters HK, Kapust RB, Li M, Wlodawer A, Waugh DS: Structural basis for the substrate specificity of tobacco etch virus protease. In: J. Biol. Chem. 277. Jahrgang, Nr. 52, Dezember 2002, S. 50564–72, doi:10.1074/jbc.M207224200, PMID 12377789 (englisch).

- ↑ Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A: MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. In: Nucleic Acids Res. 40. Jahrgang, Database issue, Januar 2012, S. D343–50, doi:10.1093/nar/gkr987, PMID 22086950, PMC 3245014 (freier Volltext) – (englisch).

- ↑ Bazan JF, Fletterick RJ: Viral cysteine proteases are homologous to the trypsin-like family of serine proteases: structural and functional implications. In: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85. Jahrgang, Nr. 21, November 1988, S. 7872–6, doi:10.1073/pnas.85.21.7872, PMID 3186696, PMC 282299 (freier Volltext), bibcode:1988PNAS...85.7872B (englisch).

- ↑ Tyndall JD, Nall T, Fairlie DP: Proteases universally recognize beta strands in their active sites. In: Chem. Rev. 105. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, März 2005, S. 973–99, doi:10.1021/cr040669e, PMID 15755082 (englisch).

- ↑ Parks TD, Leuther KK, Howard ED, Johnston SA, Dougherty WG: Release of proteins and peptides from fusion proteins using a recombinant plant virus proteinase. In: Anal. Biochem. 216. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, Februar 1994, S. 413–7, doi:10.1006/abio.1994.1060, PMID 8179197 (englisch).

- ↑ Yi L, Gebhard MC, Li Q, Taft JM, Georgiou G, Iverson BL: Engineering of TEV protease variants by yeast ER sequestration screening (YESS) of combinatorial libraries. In: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110. Jahrgang, Nr. 18, April 2013, S. 7229–34, doi:10.1073/pnas.1215994110, PMID 23589865, PMC 3645551 (freier Volltext), bibcode:2013PNAS..110.7229Y (englisch).

- ↑ Renicke C, Spadaccini R, Taxis C: A tobacco etch virus protease with increased substrate tolerance at the P1' position. In: PLOS ONE. 8. Jahrgang, Nr. 6, 2013, S. e67915, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067915, PMID 23826349, PMC 3691164 (freier Volltext), bibcode:2013PLoSO...867915R (englisch).

- ↑ Verhoeven KD, Altstadt OC, Savinov SN: Intracellular detection and evolution of site-specific proteases using a genetic selection system. In: Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 166. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, März 2012, S. 1340–54, doi:10.1007/s12010-011-9522-6, PMID 22270548 (englisch).

- ↑ Nguyen B-N, Tieves F, Neusius FG, Götzke H, Schmitt L & Schwarz C: Numaswitch, a biochemical platform for the efficient production of disulfide-rich pepteins. Hrsg.: Frontiers in Drug Discovery. Nr. 3:1082058, 2023, doi:10.3389/fddsv.2023.1082058 (englisch).

- ↑ Kapust RB, Tözsér J, Fox JD, Anderson DE, Cherry S, Copeland TD, Waugh DS: Tobacco etch virus protease: mechanism of autolysis and rational design of stable mutants with wild-type catalytic proficiency. In: Protein Eng. 14. Jahrgang, Nr. 12, Dezember 2001, S. 993–1000, doi:10.1093/protein/14.12.993, PMID 11809930 (englisch).

- ↑ Nallamsetty S, Kapust RB, Tözsér J, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Copeland TD, Waugh DS: Efficient site-specific processing of fusion proteins by tobacco vein mottling virus protease in vivo and in vitro. In: Protein Expr. Purif. 38. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, November 2004, S. 108–115, doi:10.1016/j.pep.2004.08.016, PMID 15477088 (englisch).

- ↑ Cabrita LD, Gilis D, Robertson AL, Dehouck Y, Rooman M, Bottomley SP: Enhancing the stability and solubility of TEV protease using in silico design. In: Protein Sci. 16. Jahrgang, Nr. 11, 2007, S. 2360–7, doi:10.1110/ps.072822507, PMID 17905838, PMC 2211701 (freier Volltext) – (englisch).

- ↑ Correnti CE, Gewe MM, Mehlin C, Bandaranayake AD, Johnsen WA, Rupert PB, Brusniak MY, Clarke M, Burke SE, De Van Der Schueren W, Pilat K, Turnbaugh SM, May D, Watson A, Chan MK, Bahl CD, Olson JM, Strong RK: Screening, large-scale production and structure-based classification of cystine-dense peptides. In: Nat Struct Mol Biol. 25. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, 2018, S. 270–278, doi:10.1038/s41594-018-0033-9, PMID 29483648, PMC 5840021 (freier Volltext) – (englisch).

- ↑ Keeble AH, Turkki P, Stokes S, Khairil Anuar IN, Rahikainen R, Hytönen VP, Howarth M: Approaching infinite affinity through engineering of peptide-protein interaction. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116. Jahrgang, Nr. 52, Dezember 2019, S. 26523–26533, doi:10.1073/pnas.1909653116, PMID 31822621, PMC 6936558 (freier Volltext), bibcode:2019PNAS..11626523K (englisch).